Spadina Literary Review — edition 20 page 09

fiction

Azad and Houda

by Amir Darwish

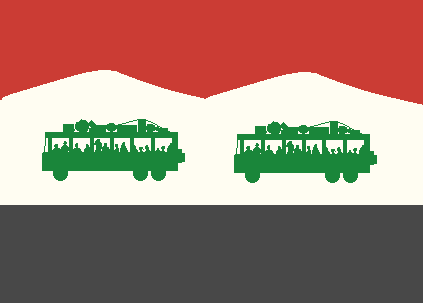

Corpses each side of road. Men with guns. A toddler walks alone, shedding a river of tears. Passengers cover their noses as smoke thickens from burning cars. Endless queues of people wait to cross the border into safety — men, women, children, some disabled.

As the bus accelerates into Turkey, trees line the road, densely, with hardly a space between them. Grey mountains appear.

My name is Houda. A woman escaping from Syria. At first I thought the war would last only a few weeks, then a few months. Now it has been years. I had a dream last night where rockets turned into sparrows and carried messages between lovers, where bullets became roses.

In our bus, people sit cramped on each other’s laps. I am unlucky as the girl who sits on my knee is chubby. I cannot feel my leg anymore. Her breath stinks. The bus is about to collapse with too many people.

“Too complex to decipher…” a man on the radio is saying. Since this started, Syria has become a world leader in the production of political analysts, activists, political scientists, geopolitical strategists.

“We have passed the danger points,” a man shouts. “Please slow down! My family are scared.”

The driver does not respond.

Everyone is here for a reason. Everyone weighed their losses and gains then found the risk from running away was lower than the risk from staying put. Everyone speaks of their homes back in Syria, everyone’s desire is for the war to end so they can go back.

An endless woods extends ahead of us with no humans in sight.

“Now we’re really in Turkey — away from Syria!” shouts the driver.

Cheers. Applause. Loud whistles fill the bus. No more war zone. My niqab falls off as I cheer. Quickly I get it back in place, but not quick enough to prevent the guy next to me to take a full glimpse. He is a good-looking guy with a cheeky smile.

“All write your names on a piece of paper and give it to me,” the driver demands.

When my turn comes, I open the paper wide, making sure the good-looking guy sees. I write, “Houda.” I pass the paper to him and watch as he writes “Azad.” His thick black hair looks even darker as the sun hits its surface. His right trouser pocket is fat with sunflower seeds, which he has been eating since the start of our bus journey. Azad’s cappuccino-coloured skin looks healthier than mine. He has thick eyebrows and lashes. And thick lips, a little cracked from dryness and thirst. He has long legs.

Suddenly, the driver asks us to get out. “Someone else will take over from here.”

There are as many as fifty people in our group. We sit in the middle of nowhere, awaiting that ‘someone else.’

Scent of pine and roses. Odour of animal and human excrement. From the latter I understand that those who escape the war in Syria must often pass by this spot, and must need to stay here for some time.

The sea is close enough that we hear waves hitting the shore. Out in that sea, lifeboats fetch people back to the shore. Some are dead, others have survived, all have tried to cross to Greece but failed. I contemplate which of these destinies awaits me.