Spadina Literary Review — edition 6 page 11

.../

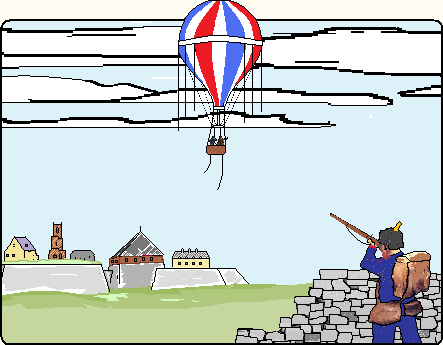

Octave Crémazie was poor. Aside from pots and crockery, he had no property the socialists could nationalize. He was employed, nominally, as a sales agent for a bookseller that barely stayed afloat during the siege. While some mail was leaving Paris via hot-air balloons, no mail was coming in, therefore Crémazie’s brothers had no way to send him money. He had to borrow from local acquaintances (we don’t know who all) to survive day to day. His grip on the petit bourgeois rung on the ladder of life was precarious, which probably gave him all the more motive to denounce proletarian mutiny. Crémazie, by the way, liked to suppose he had the bearing of a retired military officer — a fancy that was based on the come-ons of Paris coachmen, as in: “You desire a lift today, mon capitaine?”

It wasn't easy getting the mail out

Crémazie wanted the government to reverse its vaunted policy of freedom of the press which led directly, he felt, to the obscene caricatures of the ex-imperial family now being hawked on every street corner. The ex-empress Eugenie — a saint in Crémazie’s opinion — was illustrated in naked, lewd postures. Scruffy vendors, the dregs of humanity, and even their kids, cried out, “Read all about the empress’s lovers, her orgies! Ten cents!” Crémazie was outraged. He returned to the topic several times.

By mid-October, seven weeks into the siege, he complained of how hard life was getting for people of low income. When he spoke about low income, he was implicitly pointing to himself. His own cost of food had already climbed 25%, he figured. To add to the general misery, it rained a lot that month:

It is really painful to see hundreds of poor women, working women and bourgeois women, forced to form queues at the doors of the municipal butchers. Several of these mothers of families fell sick from waiting five or six hours, their feet in the mud and their clothes drenched, for the meagre rations that the government accords each person.