Spadina Literary Review — edition 6 page 09

re verse

Octave Crémazie's War Journal

by Ian Allaby

Aside from letters home, Octave Crémazie’s Journal of the Siege of Paris was the only writing the ex-poet produced during his so-called “exile” from Canada — his seventeen wraith-like years living in France under a false name. He didn’t intend the journal for publication. It was more like a lifeline: writing it gave him a sense of connection, as if he were recounting his experiences to his brothers round the hearth in Quebec City, instead of being trapped in Paris encircled by Prussian troops. It was September, 1870, the Franco-Prussian War. The Prussians had cut the roads and rails, no supplies were squeezing through. Crémazie at first believed the siege would be brief — surely the rest of France would gallop to the city's rescue — but instead the siege dragged on for over four months, bringing Crémazie and all Paris to the brink of starvation.

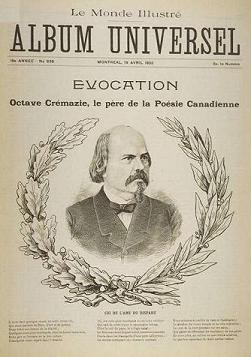

Le Monde illustré called Crémazie

“the father of Canadian poetry”

In Quebec City, Octave Crémazie had been a cultural hero, albeit a secretly troubled one. He had been a partner with his brother Joseph in a bookstore in the upper town. Octave was supposedly the one of the pair who was good with numbers. The shop was a hang-out for the literary set and it turned out that Octave could summon up a few verses himself when he put his mind to it. He was first published in 1849 in a paper edited by his eldest brother, Jacques Crémazie. Octave’s poems subsequently appeared in other newspapers where, frankly, his bookstore was a frequent advertizer. Octave Crémazie had a leg up, no doubt, but the essential point is that he was a hit. He became the first French-Canadian poet ever to win a significant following.

He did that by being a drapeau-waver without being a separatist. (Crémazie abhorred any whiff of rebellion.) He wrote about old soldiers, the forefathers, the heroic aïeux, who spilled their blood in defence of New France until, shamefully, old France left them to their fate. This narrative contained just the right mix of self-esteem and self-pity to stir the soul of French Canadians (a warrior race! abandoned!) who were laboring to build a new identity after three generations as voiceless internees of the British Empire. When Octave Crémazie bolted for France — I’ll get to that story — the literate levels of Quebec society were palpably shocked and dismayed. Nevertheless, as late as 1906, 27 years after Crémazie’s death, a crowd of 30,000 showed up for the unveiling of his statue in Montreal’s Carré St.-Louis.

The daily entries in Crémazie's Journal of the Siege of Paris adhere to a routine structure. You soon pick up on the ex-poet's experience of confinement in the sealed-off city. An inveterate Canadian, he begins each entry with a weather report. It's mild, it's rainy, it's cold beyond belief, or whatever. Next come accounts of military and political developments, plus whatever rumors are in the air, and, with growing concern, the cost of food. To most modern readers, Crémazie will also seem constricted on the ideological level by being too monarchist and too Catholic by a country mile. He’s not a character that’s easy to sympathize with. You have to make allowances.