Spadina Literary Review — edition 4 page 05

.../

Certainly Tekahionwake unleashes a barrage of poetic defamation upon the Huron: in her verses they are “vile,” “vicious,” and “craven” people, they speak “evil Huron speech.” She probably didn’t feel much pressure to present a more balanced picture, since very few Huron attended her concerts. Most of them had been wiped out by the Mohawk and other Iroquois tribes two and a half centuries earlier.

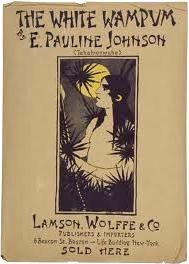

Poster promoting

The White Wampum

At that time the Mohawk inhabited what is still called the Mohawk Valley in present-day New York State. Newly furnished with guns from the Dutch at Albany, a thousand Mohawk and Seneca warriors launched a surprise attack on Huronia in mid-March of 1649. The Huron fell back in panic. Many took refuge on Christian Island, off the tip of the Penetang Peninsula, where they suffered massive losses from disease and famine during the subsequent ghastly winter. At spring breakup, the survivors scattered as refugees to other tribes or made their way to New France. The burnt, abandoned villages of Huronia sank beneath the soil.

Tekahionwake’s second Huron-slagging poem is the 70-line “Ojistoh”. Its narrator, Ojistoh, is the wife of (again!) a heroic Mohawk chief. Now, the Hurons long for revenge against this Mohawk who has cast so many of their fellow tribesmen into graves. But they are terrified of him! They dare no war-path! Instead, they kidnap his darling wife Ojistoh. As fate would have it, the Huron ruffian Ojistoh most despises turns out to be the one who gets to whisk her away.

And we two rode, rode as a sea wind-chased,

I, bound with buckskin to his hated waist,

He, sneering, laughing, jeering, while he lashed

The horse to foam, as on and on we dashed.

Well, the Huron didn’t have horses. They travelled by foot and water. Ontario was forest. Anyway, as her captor gallops toward the Huron camp, Ojistoh deploys her wiles:

I smiled, and laid my cheek against his back:

“Loose thou my hands,” I said. “This pace let slack.

Forget we now that thou and I are foes.

I like thee well, and wish to clasp thee close;

I like the courage of thine eye and brow;

I like thee better than my Mohawk now.”

So the fool cuts her bindings.

My hand crept up the buckskin of his belt;

His knife hilt in my burning palm I felt;

One hand caressed his cheek, the other drew

The weapon softly — “I love you, love you,”

I whispered, “love you as my life.”

And — buried in his back his scalping knife.

An audience might want some respite after all that bloodshed, so what Tekahionwake served up next was a "lyric" segment that included a mixed bag of nature poems, Jesus poems, nonce poems, and canoe poems such as her famous "The Song My Paddle Sings." She also had some love poems. Generally her love poems had a forsaken air about them, and the most grievous of them were assuredly not included in the stage show. In her personal life Tekahionwake had flings and was even nominally engaged for a couple years, but marriage was not in the cards for her.