Spadina Literary Review — edition 35 page 18

memoir

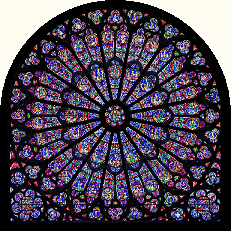

My Rose Window

by James Nelson

It was like a kick in the stomach when I received a BBC alert on my phone last year in April telling of the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

The Great Rose

I felt physically sick watching the news reports as the spire collapsed and the fire consumed those ancient timbers and who knows how much irreplaceable artwork. The drone shot of the entire cathedral roofless and blazing from end to end filled me with despair. I thought it was a total loss.

For those with a religious tie to the building, I guess their God was on holidays when he allowed one of the greatest monuments on Earth to be almost completely destroyed.

My personal association with Notre Dame goes back a few years. I studied the cathedral’s north rose window, also called the Great Rose Window, in art class on my way to securing my “Leaving Certificate” — a credential that has passed into history in Ireland, but used to crown the successful completion of six years of secondary school.

My art teacher, who assigned me the Great Rose as my project, was an American-born hippie who stretched the curriculum to its absolute limit to give her students the most eclectic artistic experience possible. Architecture was not strictly on the syllabus, but the Department of Education had to accept it as an art form worthy of study.

Without actually traveling to Paris, I gathered as much information on my subject as was possible in those days long before the Internet.

The foundation stone for Notre Dame was laid in the year 1163 but the nave was not completed until 1250, and it took a few years more before the north rose window was finished in 1255, which happened to be approximately the crest of the High Middle Ages. At one time I knew the exact diameter of that window, its radius, circumference, depth, load-bearing capacity, the number of fans radiating from the roundel, and exactly which images were contained in which spot. I remember drawing those images in as much detail as I could, all of them scenes from the life of Jesus and the angels and saints. Thanks to a BBC documentary, I even knew the songs that the masons and carpenters sang. I loved learning about it all, and I got an A+ in the exam.

Rose windows are a notable feature of Gothic cathedrals especially in northern France. At Notre Dame the north rose was the biggest and most intricate of three roses over three different portals. It became the standard by which all other Gothic rose windows were measured.

I recall some of the nomenclature, for example how there was the central roundel with spoke-like mullions radiating out, and at the outer edge were the spangles glittering around and underneath the work.

To have large glass windows piercing the walls of these great late medieval cathedrals was an incredible feat of engineering. The glazer and the engineer/stonemason would collaborate in calculating the expected load atop the rose and how far they could push its diameter without risking collapse. The window’s wheel shape helped to disperse the load pressing down. The mullions, despite their tracery-like quality, were excellent load-dispersal features.

The glassmakers of the time, using methods perhaps passed down to them, or perhaps newly discovered, achieved in their stained glass a breathtaking level of detail still crystal-clear to us after more than eight hundred years.

The individual pieces of glass were either formed in a molten state or cut to shape. Then the craftsmen mixed crushed coloured glass with wine or even urine to paint images and traceries on the glass, before heating it to an exact temperature to fix the images. They had a meticulous practical understanding of chemical reactions, though the kind of systematized knowledge such as in the Periodic Table might be far in the future.

Hold on a second! What was that about urine?