Spadina Literary Review — edition 8 page 13

.../

In that magical hunter-gatherer world, along with the animal costumes and dances and the chanting on the trodden earth of the proto-village-square, along with that there were animal stories told round the fire by the storytellers. Those were the days of the real storytellers, the first ones. In their stories the animals, with their privileged connection, were our teachers.

Traces of those themes survived thru the ages. Aesop’s fables in classical Greece are a pale derivative, but they do point to the long anterior tradition of animals delivering lessons.

The tradition is visible still in the early Christian era, whence it eventually would travel forward into modern science. The famous example is the anonymous Physiologus composed in Alexandria, Egypt. Now, Alexandria was a new-age hotbed of bible study while Egypt had been a hotbed of animal cults and animal-gods for millennia. You might call this book a zoological work, since it presented lore on a gallery of forty or so animals, but the emphasis was on animals as symbols of a deeper reality. The animal kingdom was a sort of morality play which God (the playwright) had packed with codes and messages for humans.

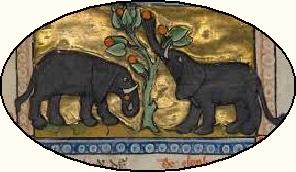

Elephants cavorting

Take the phoenix, a bird that we would call mythical. The phoenix is thought to dwell in faraway exotic India until its final days when it migrates (makes a pilgrimage?) to Egypt, more precisely to Heliopolis (ancient city of the priesthood of the sun god) where it alights on an altar and bursts into flame. Three days later, a new, born-again phoenix emerges from the ashes and flies back to India. This demonstration in nature confirms that Christ rose from the dead in three days. Just like the bible says.

The tales of Physiologus were carried forward in Europe from one generation of copyists to another for a thousand years, culminating in the fantastical illuminated bestiaries, or animal books, compiled by the monks of the High Middle Ages.

The monks found animal mating habits particularly interesting. Take the elephant as portrayed in the likes of the 12th-century Aberdeen Bestiary. Elephants were so ungainly that to have a fair chance of copulating they had to travel to the Garden of Eden, where grows the mandrake plant (thought to be an aphrodisiac and/or intoxicant). The female elephant plucks a mandrake, tastes it, and offers it to her companion, who thereby gets all excited and the big event finally takes place. The Adam-and-Eve parallel is obvious, but we might note that, unlike mankind, the elephants are allowed to return to Eden and sinlessly sample the wares.