Spadina Literary Review — edition 7 page 22

.../

Jang Jin-sung portrays North Korea as a technically incompetent society, marked by breakdowns and blackouts, where the elite live in luxury while the workers get the crumbs, if that. He recounts North Korea’s sins such as naval provocations and the kidnapping of foreign citizens. There are no corresponding tales of Western subterfuges against North Korea, altho as a propaganda worker you might expect Jang to be informed on that topic.

To Jang, the West’s only flaw is that it is easily suckered into sending North Korea aid packages that end up in the hands of the cadres.

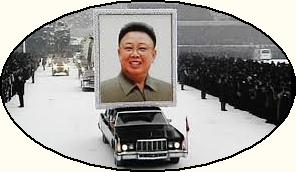

Kim Jong-Il, sponsor of longevity research

Eventually I decided to treat this book as reality-based propaganda entertainment — so, propaga-tainment? Whether this does justice to Jang, I don’t know. I’m just saying, that was my attitude for this particular book.

Jang had been a music student but his trajectory changed in 1990 when he found in his father’s bookcase a limited-edition translation of the Collected Works of Lord Byron — limited-edition, because it was available only to members of the ruling elite. It would be Byron, wouldn’t it? — a Western poet whose name even today is a byword for romantic adventure. The translation must have been fabulous because Byron, says Jang, “awakened in me a sense of literary sublimity that surpassed music. These poems were proof that emotions could be experienced in a personal sphere that did not include the Leader.”

So Jang tried his own hand at poetry and launched a new career for himself by contributing to a poetry collection that earned Kim’s nod of approval.

Kim’s father had favored the propaganda novel, a form apt for conveying the grand sweep of revolutionary history. But Kim preferred poetry. A political environment emerged where, incredible to us, cadres and departments competed for the Dear Leader’s favor on the basis of their verse-craft.

Jang in 1999 at age 28 was assigned the challenging task of creating, under an assumed South Korean name, an epic poem to promote the idea that North Korea’s songun (“military first”) policy was meant to protect both North and South Korea. In the resulting poem, entitled “Spring Rests on the Gun Barrel of the Lord,” the great Kim Il-sung takes the gun he supposedly used to chase the Japanese out of the entire Korean peninsula in World War II and bequeaths it to his son Kim Jong-il:

So this is the Gun

that in the hands of an inferior man

can only commit murder,

but, when wielded by a great man,

can overcome anything.

Jang’s poem was published nationwide and secured the author the prestigious above-mentioned invitation to the Dear Leader’s dinner table.

A turning point for Jang Jin-sung was in 2000 when he was granted a week off to visit his hometown just 66 km south of the capital Pyongyang. The place was in gruesome disarray. After years of near-starvation, his old friends were ghosts of their former selves. Homeless people filled the parks. A corpse squad cleared away the bodies of those who died on the streets. Official posters everywhere screamed death threats for anyone who hoarded, or gossiped, or disobeyed traffic rules. In the marketplace, Jang witnessed the execution, by firing squad, of a starving farmer who had stolen a sack of rice.