Spadina Literary Review — edition 5 page 15

.../

In 1844 when the Empire transferred our Oliver Goldsmith to Hong Kong, the St. John Morning News reported that 2,000 people gathered to see him off — a rare moment in the spotlight for Oliver. The locals, it turns out, especially admired Oliver’s skill as a skater who, tho middle-aged, could etch his name in florid curves on the ice. Speeches were made, the crowd cheered, the band struck up “God Save the Queen” and then “Should auld acquaintance be forgot” as the steamer slipped from St. John Harbour. It travelled down the Maine coast, past Hat Island where Oliver had been marooned in 1818. At New York City, Oliver boarded a newly-built clipper, the Howqua, owned by a certain Abiel A. Low, whose fortune had been made in the opium trade.

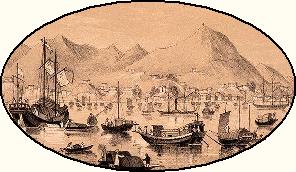

Hong Kong, said Oliver, was “the “back kitchen of Beelzebub.” Its raison d’être was to provide a secure harbor for merchants running opium into China. It was a steamy, lawless environment. The waters were infested with pirates, the land with bandits, and the colony’s top officials were at each other’s throats. Oliver found his duty “oppressive in the extreme.”

Beelzebub's back kitchen

Up in Guangdong there were always mobs tossing stones at English businessmen. After one such incident in early 1847 the governor of Hong Kong blew his top and ordered a thousand soldiers up the Pearl River to teach the Chinese a lesson in civilized behavior. Oliver’s task was to quickly hire and stock the boats for the expedition. But he was finding the work too much for him. That summer, Oliver suffered a probably minor stroke. His health deteriorated steadily thereafter until the Medical Board ordered his removal in February 1848.

The Empire still had not done with Oliver. It shuffled him off to Newfoundland, which at least was light duty. In 1853 he was promoted to Deputy Commissary General, which he considered the equivalent of the military rank of Major. It had taken 42½ years of service to get that far, he groused. The next year, Oliver was dispatched urgently to Corfu, a British-held island in the Adriatic, where he had to accommodate regiments transiting to the Empire’s latest glory, the Crimean War. This really was the end for Oliver. He hadn't the stamina. Oliver resigned and left Corfu in early 1855. He was placed on half pay — a sort of retirement benefit — and lived apparently uneventfully with his sister in Liverpool until his death in 1861. Since the old necropolis where Oliver was buried has itself been buried under a public park named Grant Gardens, Oliver's grave there is not visitable, at least not as an identifiable spot.