Spadina Literary Review — edition 25 page 13

fiction

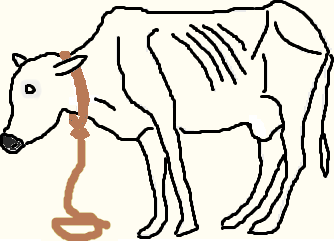

The Cow

by Khalid Bekkaoui

On a Friday afternoon, two weeks before Ramadan, Kanfoudi Boulakrouch was in his flat teaching the rules of the science of Koranic recitation to his three guests: the owner of a halal food chain in Dusseldorf, a manager of a textile factory, and the financial officer of a big import-export company. Kanfoudi supplied his students with copious mesmerizing information on the idiosyncrasies of Warsh and Hafs recitations and the differences between them. If a student mispronounced a word, he would turn aside with irritation, contorting his face involuntarily in a grotesque grimace. Kanfoudi derived an infantile, almost morbid, satisfaction in correcting his students’ mistakes.

For recitation practice, Kanfoudi chose Surat Al Baqara, that is, The Cow, the longest surat in the Koran. He could recite from memory the entire surat as well as explain it minutely and eloquently. For the sake of his audience’s edification and the purpose of today’s teaching, he narrated the story of Adam and Eve’s disobedience to God in Al Baqara and their fall from the Garden of Eden. Then Kanfoudi moved to the story of the people who were requested by God to sacrifice a cow. Instead of complying immediately with God’s command, they began procrastinating and demanded more and more specifications about the shape and colour of the cow until God designated a cow that was very dear to them. They finally slaughtered the cow, yet not without great grief and grudge.

By the time Kanfoudi was enthusiastically expounding the moral of the parables, the door of his flat buzzed, twice. Then one more buzz, sharp and long. His heart nearly leapt out of his chest. He didn’t want to receive any visit, not today, not now. Opening the window and leaning out, he saw a turbaned head fringed with gray, thinning hair. It was a man in a pale blue djellaba, a traditional cloak. It was his father. Kanfoudi hated this impromptu visit. It would spoil everything, the lesson, the food he had prepared for this occasion, and, most importantly, the favour he intended to ask of the immigrant from Dusseldorf. He was planning at the end of the lesson to ask him to fund the digging of a well to supply water to a mosque in the remote village of Dchar Karkar. Water was expected to be at a depth of at least forty meters, which would bring the cost to a high sum. Kanfoudi was sure the man from Dusseldorf would donate the required money. And he was optimistic that the other guests would contribute for the purchase of a pump and a high-horsepower diesel engine. But now all his plan for supplying the mosque of Dchar Karkar with water ran the risk of going awry.

Kanfoudi scurried to the kitchen and instructed his wife to usher his father into a room and detain him by all means from coming into the living room until the guests had left. About half an hour later, however, the living room curtains were briskly pulled aside, and in stepped the figure of Kanfoudi’s father, a tall, stout man with bold mountainous features.

“Salamu alaykum! Peace be with you,” he snorted cheerfully, flashing a good-humoured smile and strolling across the living room. “I cannot hear the Koran being recited without joining in.” He extended his huge hand to his son’s guests to shake.